American Chemical Society10.25.23

Leonardo da Vinci is renowned to this day for innovations in fields across the arts and sciences. Now, new analyses published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society show that his taste for experimentation extended even to the base layers underneath his paintings. Surprisingly, samples from both the “Mona Lisa” and the “Last Supper” suggest that he experimented with lead(II) oxide, causing a rare compound called plumbonacrite to form below his artworks.

An aura of mystery has surrounded the paints and pigments in da Vinci’s studio, leading scientists to scour his writings and artwork to search for clues. Many paintings from the early 1500s, including the “Mona Lisa,” were painted on wooden panels that required a thick, “ground layer” of paint to be laid down before artwork was added.

Scientists have found that while other artists typically used gesso, da Vinci experimented by laying down thick layers of lead white pigment and by infusing his oil with lead(II) oxide, an orange pigment that conferred specific drying properties to the paint above.

He used a similar technique on the wall underneath the “Last Supper” — a departure from the traditional, fresco technique used at the time. To further investigate these unique layers, Victor Gonzalez and colleagues wanted to apply updated, high-resolution analytical techniques to small samples from these two paintings.

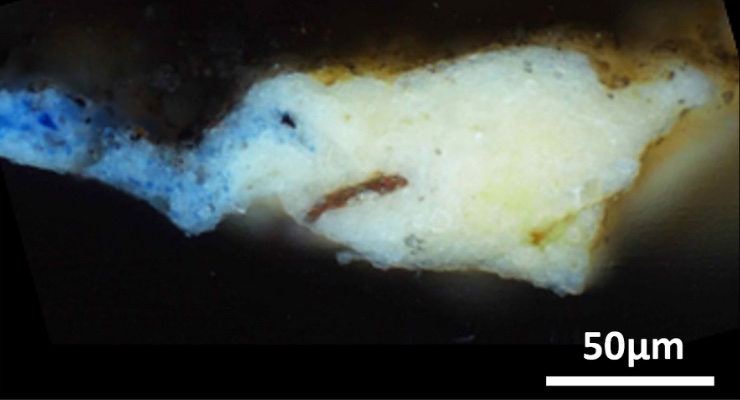

The team performed their analyses on a tiny, “microsample” previously obtained from a hidden corner of the “Mona Lisa,” as well as 17 microsamples obtained from across the surface of the “Last Supper.”

Using X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy techniques, they determined that the ground layers of these artworks not only contained oil and lead white, but also a much rarer lead compound: plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)O(OH)2). This material had not previously been detected in Italian Renaissance paintings, though it’d been found in later paintings by Rembrandt in the 1600s.

Plumbonacrite is only stable under alkaline conditions, suggesting that it formed from a reaction between the oil and lead(II) oxide (PbO). Intact grains of PbO were also found in most of the samples taken from the “Last Supper.”

While painters were known to add lead oxides to pigments to help them dry, the technique has not been proved experimentally for paintings from da Vinci’s time. In fact, when the researchers searched through his writings, the only evidence they found of PbO was in reference to skin and hair remedies, even though it’s now known to be quite toxic. Though he might not have written it down, these results demonstrate that lead oxides must have had a place on the old master’s palette, and might have helped create the masterpieces we know today.

The authors acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions.

An aura of mystery has surrounded the paints and pigments in da Vinci’s studio, leading scientists to scour his writings and artwork to search for clues. Many paintings from the early 1500s, including the “Mona Lisa,” were painted on wooden panels that required a thick, “ground layer” of paint to be laid down before artwork was added.

Scientists have found that while other artists typically used gesso, da Vinci experimented by laying down thick layers of lead white pigment and by infusing his oil with lead(II) oxide, an orange pigment that conferred specific drying properties to the paint above.

He used a similar technique on the wall underneath the “Last Supper” — a departure from the traditional, fresco technique used at the time. To further investigate these unique layers, Victor Gonzalez and colleagues wanted to apply updated, high-resolution analytical techniques to small samples from these two paintings.

The team performed their analyses on a tiny, “microsample” previously obtained from a hidden corner of the “Mona Lisa,” as well as 17 microsamples obtained from across the surface of the “Last Supper.”

Using X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy techniques, they determined that the ground layers of these artworks not only contained oil and lead white, but also a much rarer lead compound: plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)O(OH)2). This material had not previously been detected in Italian Renaissance paintings, though it’d been found in later paintings by Rembrandt in the 1600s.

Plumbonacrite is only stable under alkaline conditions, suggesting that it formed from a reaction between the oil and lead(II) oxide (PbO). Intact grains of PbO were also found in most of the samples taken from the “Last Supper.”

While painters were known to add lead oxides to pigments to help them dry, the technique has not been proved experimentally for paintings from da Vinci’s time. In fact, when the researchers searched through his writings, the only evidence they found of PbO was in reference to skin and hair remedies, even though it’s now known to be quite toxic. Though he might not have written it down, these results demonstrate that lead oxides must have had a place on the old master’s palette, and might have helped create the masterpieces we know today.

The authors acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions.