Vladislav Vorotnikov, Russia Correspondent03.08.19

Following an announcement that car makers with finished vehicle assembly plants in Russia may be obligated to use only coatings of Russian origin, there is word that the same measure is being considered for the furniture industry.

In the meantime, Russian chemical companies are commencing new raw materials production projects for the coating industry, rushing to take advantage of the national import-replacement programs.

The import replacement campaign that has taken place over the past few years in Russia reached an unprecedented scale in late 2018, on the background of new sanctions and complaints from the Russian coating manufacturers that some Western companies could be engaged in “dumping” on the Russian market.

Assault on PPG

U.S.-based PPG began dumping, according to a statement posted by the Russian Gazette, the official publication of the Russian government, in late 2018.

The Russian Gazette warned that this activity could not only destroy some production of coatings in Russia, but also, in the future, bring instability.

In 2018, PPG supplied basecoat to Russian steel giant Severstal and other metallurgical companies in the country at a price that was 40 percent lower than market average: Between €4.3 and €4.6 per kg, the Russian Gazette reported.

At least several Russian coatings producers were scarred by this fact and demanded the government protect the domestic market.

For example, Vladimir Dyunin, advisor of the general director of the Russian coating producer Yarli, said his company had been gradually developing over the past few years and is able to compete with the world’s biggest companies price and quality wise, but the competitive environment on the Russian market in 2018 “was not completely fair.”

Dyunin explained that companies like PPG “have enormous volumes” and, moreover, are granted various bonuses for building their production facilities in Russia.

According to Dyunin, Yarli believes that PPG was applying to dump and this fact “could be checked.”

Sergey Perevoschikov, deputy general director of the Russian coating company Top Praim Industry, expressed confidence that the threat to the Russian coating industry from PPG’s actions was “very strong.”

Perevoschikov explained that it was unclear how PPG could provide discounts when production costs have been increasing all over the supply chain and there was a shortage of raw materials on the global market.

PPG could act in the interest of the U.S. government, the Russian Gazette claimed.

The company said on its website that it is keen to be actively involved in the political process, while the “U.S. government policy in relation to Russia is well-known,” the Russian Gazette stressed.

In this context, the Russian Gazette warned that it isn’t a wise step for Russian companies to use PPG production because it could push Russian manufacturers out of the market and, with the introduction of new economic sanctions against Russia, the local companies could be eventually left without any coatings at all.

However, so far there has been no official request for the Russian Federal Antidumping Service to open an anti-dumping investigation against PPG.

Companies with Russian subsidiaries – such as PPG, Henkel and Tikkurila – technically have all the same rights as the companies of Russian origin, according to Alexander Ivanov, a Moscow-based international arbitration lawyer.

While the Russian government can – and most likely will – keep taking certain steps aimed to decrease the presence of imported coating on the domestic market, there is no chance that some differences in legal status could be made between Russian and foreign companies.

This means that all foreign companies that localized their production in Russia could seek state aid from the government and participate in competitive bidding procedures using the same rules as the Russian companies. Any changes in that regime would create a very dangerous precedent for the entire investments environment in the Russian economy, Ivanov added.

There are some actions aimed at reducing the share of imported coatings on the Russian market.

Just recently, the Russian Industry and Trade Ministry promised to seek a complete ban on purchasing any furniture made of imported components within the government state procurement program. Nearly 10 percent of furniture in Russia is purchased within the state procurement programs, the Association of Furniture and Woodworking Enterprises of Russia estimated.

However, nearly all of the Russian companies seek an opportunity – from time to time – to participate in these state procurement programs. If changes are applied, it could significantly impact the import of some categories of coatings in the country.

“PPG holds itself to the highest ethical standards and acts in strict compliance with all applicable export control laws and regulations,” Michael Shukov, general manager of PPG Industries LLC in Russia said in response to the allegations posted in the Russian Gazette.

“The principle of fair competition has always been at the heart of PPG throughout its 135-year history,” Shukov continued. “PPG is proud to operate in Russia for nearly a half century, and during that time has become the supplier for leading industrial enterprises in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States.

“In 2017, PPG celebrated the opening of a €45 million ($49 million) paint and coatings manufacturing facility and commercial operation in the Lipetsk region of Russia. The facility has the capacity to produce about 25 million liters (6.6 million gallons) of coatings at full capacity,” Shukov added.

Looking deeper

Several new projects in the area of raw materials for coatings production have been announced in Russia during recent months.

Bashkir Soda Ash Company, the biggest producer of soda ash in Russia, has embarked on an investment program from 2024 to 2026, planning to build a start producing around 100,000 metric tons of titanium dioxide (TiO2) in Kazakhstan.

The company plans to invest around $900 million in the project and take advantage of problems surrounding Crimean Titanium, Russia’s major supplier of TiO2.

In mid-2018, ecological problems forced Crimean Titanium to suspend production for more than a month.

According to Centrlak, the Russian association of coating producers, the technological process at the Crimean Titanium is outdated and the production doesn’t match the requirements of the Russian coatings production.

Crimean Titanium earlier revealed plans to invest Rub30 billion ($450 million) to perform a thorough modernization in the coming several years.

Russian newspaper Kommersant, citing its own sources, reported that Crimean Titanium could stop production completely, unless it is able to resolve ecological issues.

Marina Bortova, deputy director of the Bashkir Soda Ash Company said that the company wants to “meet the demand for high-quality TiO2 on the Russian market” by 100 percent.

The company could receive state support from the the Kazak National Welfare Fund, Samruk Kizina, Bortova added, while not providing any further details.

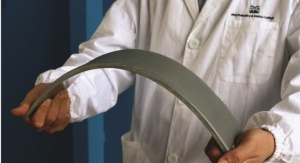

In early 2019, Russian chemical company Sibur announced plans to build a plant for the production of 45,000 metric tons of maleic anhydride per year.

In a statement, Sibur said this raw material was not produced in Russia. Sibur added that it plans to make the plant operational by 2021.

In the meantime, Russian chemical companies are commencing new raw materials production projects for the coating industry, rushing to take advantage of the national import-replacement programs.

The import replacement campaign that has taken place over the past few years in Russia reached an unprecedented scale in late 2018, on the background of new sanctions and complaints from the Russian coating manufacturers that some Western companies could be engaged in “dumping” on the Russian market.

Assault on PPG

U.S.-based PPG began dumping, according to a statement posted by the Russian Gazette, the official publication of the Russian government, in late 2018.

The Russian Gazette warned that this activity could not only destroy some production of coatings in Russia, but also, in the future, bring instability.

In 2018, PPG supplied basecoat to Russian steel giant Severstal and other metallurgical companies in the country at a price that was 40 percent lower than market average: Between €4.3 and €4.6 per kg, the Russian Gazette reported.

At least several Russian coatings producers were scarred by this fact and demanded the government protect the domestic market.

For example, Vladimir Dyunin, advisor of the general director of the Russian coating producer Yarli, said his company had been gradually developing over the past few years and is able to compete with the world’s biggest companies price and quality wise, but the competitive environment on the Russian market in 2018 “was not completely fair.”

Dyunin explained that companies like PPG “have enormous volumes” and, moreover, are granted various bonuses for building their production facilities in Russia.

According to Dyunin, Yarli believes that PPG was applying to dump and this fact “could be checked.”

Sergey Perevoschikov, deputy general director of the Russian coating company Top Praim Industry, expressed confidence that the threat to the Russian coating industry from PPG’s actions was “very strong.”

Perevoschikov explained that it was unclear how PPG could provide discounts when production costs have been increasing all over the supply chain and there was a shortage of raw materials on the global market.

PPG could act in the interest of the U.S. government, the Russian Gazette claimed.

The company said on its website that it is keen to be actively involved in the political process, while the “U.S. government policy in relation to Russia is well-known,” the Russian Gazette stressed.

In this context, the Russian Gazette warned that it isn’t a wise step for Russian companies to use PPG production because it could push Russian manufacturers out of the market and, with the introduction of new economic sanctions against Russia, the local companies could be eventually left without any coatings at all.

However, so far there has been no official request for the Russian Federal Antidumping Service to open an anti-dumping investigation against PPG.

Companies with Russian subsidiaries – such as PPG, Henkel and Tikkurila – technically have all the same rights as the companies of Russian origin, according to Alexander Ivanov, a Moscow-based international arbitration lawyer.

While the Russian government can – and most likely will – keep taking certain steps aimed to decrease the presence of imported coating on the domestic market, there is no chance that some differences in legal status could be made between Russian and foreign companies.

This means that all foreign companies that localized their production in Russia could seek state aid from the government and participate in competitive bidding procedures using the same rules as the Russian companies. Any changes in that regime would create a very dangerous precedent for the entire investments environment in the Russian economy, Ivanov added.

There are some actions aimed at reducing the share of imported coatings on the Russian market.

Just recently, the Russian Industry and Trade Ministry promised to seek a complete ban on purchasing any furniture made of imported components within the government state procurement program. Nearly 10 percent of furniture in Russia is purchased within the state procurement programs, the Association of Furniture and Woodworking Enterprises of Russia estimated.

However, nearly all of the Russian companies seek an opportunity – from time to time – to participate in these state procurement programs. If changes are applied, it could significantly impact the import of some categories of coatings in the country.

“PPG holds itself to the highest ethical standards and acts in strict compliance with all applicable export control laws and regulations,” Michael Shukov, general manager of PPG Industries LLC in Russia said in response to the allegations posted in the Russian Gazette.

“The principle of fair competition has always been at the heart of PPG throughout its 135-year history,” Shukov continued. “PPG is proud to operate in Russia for nearly a half century, and during that time has become the supplier for leading industrial enterprises in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States.

“In 2017, PPG celebrated the opening of a €45 million ($49 million) paint and coatings manufacturing facility and commercial operation in the Lipetsk region of Russia. The facility has the capacity to produce about 25 million liters (6.6 million gallons) of coatings at full capacity,” Shukov added.

Looking deeper

Several new projects in the area of raw materials for coatings production have been announced in Russia during recent months.

Bashkir Soda Ash Company, the biggest producer of soda ash in Russia, has embarked on an investment program from 2024 to 2026, planning to build a start producing around 100,000 metric tons of titanium dioxide (TiO2) in Kazakhstan.

The company plans to invest around $900 million in the project and take advantage of problems surrounding Crimean Titanium, Russia’s major supplier of TiO2.

In mid-2018, ecological problems forced Crimean Titanium to suspend production for more than a month.

According to Centrlak, the Russian association of coating producers, the technological process at the Crimean Titanium is outdated and the production doesn’t match the requirements of the Russian coatings production.

Crimean Titanium earlier revealed plans to invest Rub30 billion ($450 million) to perform a thorough modernization in the coming several years.

Russian newspaper Kommersant, citing its own sources, reported that Crimean Titanium could stop production completely, unless it is able to resolve ecological issues.

Marina Bortova, deputy director of the Bashkir Soda Ash Company said that the company wants to “meet the demand for high-quality TiO2 on the Russian market” by 100 percent.

The company could receive state support from the the Kazak National Welfare Fund, Samruk Kizina, Bortova added, while not providing any further details.

In early 2019, Russian chemical company Sibur announced plans to build a plant for the production of 45,000 metric tons of maleic anhydride per year.

In a statement, Sibur said this raw material was not produced in Russia. Sibur added that it plans to make the plant operational by 2021.